Nash Stream

Goals

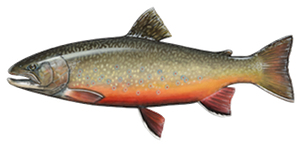

Fishing for large wild brook trout in a rushing New England stream is something every angler covets. There was a time when doing so was relatively easy. Streams were pristine and fish were plentiful. Now some are degraded and many hold fewer fish. The Nash Stream Restoration Project is changing that by restoring and reconnecting habitat so that New Hampshire's Nash Stream and its heritage brookies can reclaim their position among the region’s finest trout fisheries.

Tactics

Nash Stream, in the Connecticut River watershed, experienced a catastrophic dam break in 1969. The dam was a relic from historic log drives, and the damage to Nash Stream was made worse when well-meaning people channelized sections of the stream after the flood. We’re repairing that historic damage, rebuilding trout habitat, and reconnecting spawning tributaries to the 15-mile stream.

Imagine a large pine tree crashing down across the river. Picture the way it traps smaller wood that floats in from upstream. Eventually it creates a deep pool. A handful of wild brook trout find their way there. They grow and get bigger. That’s the way it’s supposed to work. Except at Nash Stream, the dam break flood filled in the pools and washed away the wood. So we’re rebuilding pools one log at a time, adding wood back into the system. Sometimes we build the entire log jam—maybe adding a few boulders for good measure. Other times we put the trees in upstream and let the river do the work. Either way, the trout love it.

We're also addressing stream crossings so fish can move throughout the watershed. Undersized and perched culverts can prevent fish from swimming upstream. That limits access to cooler water and important spawning habitat for trout. So we’re replacing them with structures that are nearly invisible to native fish. Doubling or tripling the size of a stream crossing makes it more resilient to flooding. High water, wood, and sediment can freely and safely pass under the road. Better still, brook trout and other native fish can easily swim past. Simulating a natural stream bed helps. That’s why we’re rebuilding entire channels boulder by boulder then filling the gaps with cobbles and gravel. If we do our job well, the finished product looks like a natural stream—loaded with plenty of resting places for native fish.

Victories

We’ve built more than a dozen log jams and placed scores of boulders and hundreds of pieces of large wood in the channel. That work restored over 6 miles of main stem habitat. Wood replenishment was also performed on nearly a mile of three perennial tributaries to Nash Stream. Native brook trout now have plenty of deep pools in which to rest and find cover. We’ve also fixed eight stream crossings on six perennial tributaries to Nash Stream and two on the main stem which reconnected over 12 miles of spawning habitat. Brookies and other native fish can now access water that they haven’t been able to get to in nearly half a century. That means more trout get to where they want to be when they need to, and ultimately better fishing for all of us.

Staff Contact

Keith Curley, kcurley@tu.org

Author of this Page

Mark Taylor, eastern communications director